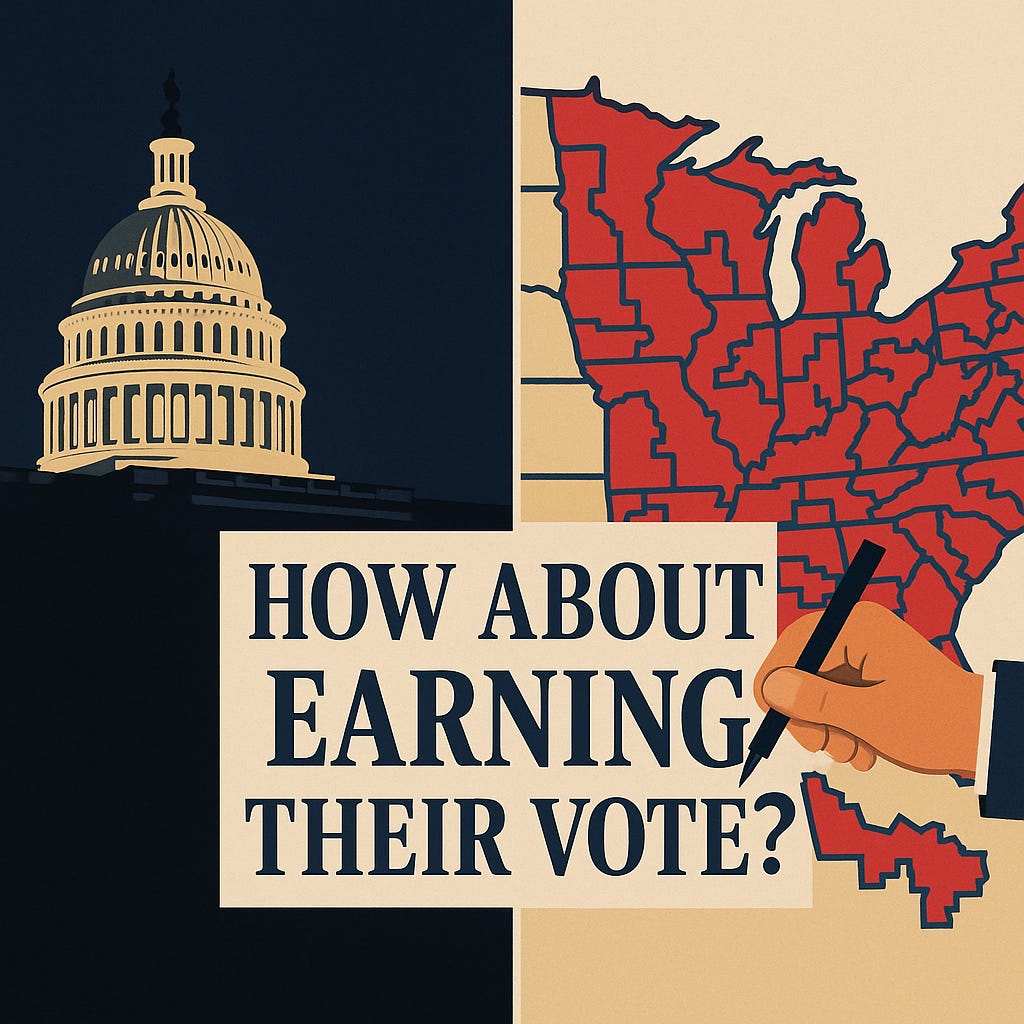

How About Earning Their Vote?

What the government shutdown, gerrymandering, and our national polarization all have in common — and the one civic habit that could fix them.

How About Earning Their Vote?

There’s a split screen in our country right now. On one side, we’re over a month into a government shutdown. On the other, a handful of states are busy gerrymandering U.S. congressional districts to secure partisan advantage.

Neither is good for the functioning of the republic. Neither reflects a healthy democracy.

Here’s a simple idea that can help fix both: EARN THEIR VOTE!

The Shutdown: Governing Means Persuading

Let’s start with the shutdown. The Senate requires 60 votes to pass most pieces of legislation — an intentional design choice meant to ensure deliberation and minority representation.1 In theory, that’s a feature, not a flaw. But these days, it’s used as an excuse for paralysis.

Predictable narratives have already been workshopped by Trump-friendly media: that this is somehow the Democrats’ fault. Sprinkle in a few pounds of disdain for “illegals,” add a dash of “woke” outrage, and the algorithms will do the rest.

But make no mistake: this shutdown is exactly what Donald Trump wants. He’s relishing every minute of it — using the moment to push permanent layoffs in what OMB Director Russell Vought openly called “Democrat-sponsored programs,” while offering only empty lip service to the millions of working poor and children now going hungry as SNAP benefits run dry. Meanwhile, the same president presses ahead with his pet project — a monument to excess we might as well call the Let Them Eat Cake Trump Royal Ballroom.

Still, that doesn’t mean the supermajority requirement in the Senate is the villain here. It’s a guardrail. It ensures that even when one party controls both chambers and the presidency, the minority still has a seat at the table. “Elections have consequences” is true — but in a representative democracy, those consequences don’t mean absolute rule by 50% + 1.

So, what’s the answer? The majority in the Senate could, at any time, earn enough votes from their colleagues across the aisle to reach that 60-vote threshold. Negotiate. Concede where necessary. Govern.

That’s not radical. That’s the system working as intended.

A Model from Utah

Jonathan Rauch, in his recent book Cross Purposes, tells the story of how Utah managed to do just that.2 In 2015, lawmakers there faced what seemed like an impossible dilemma: how to protect the rights of LGBT citizens while respecting the convictions of religious communities, particularly the LDS Church.

Instead of digging in, they talked. They listened. They built trust.

The result — the Antidiscrimination and Religious Freedom Amendment — protects LGBT Utahns from discrimination in housing and employment, while granting religious institutions exemptions consistent with their beliefs.

Here’s how I think about it: churches can not and should not make laws that discriminate against people for being gay. Nor should the state make laws that force clergy to perform ceremonies that violate their faith.

Some people on either side might find that objectionable. Too bad. That’s pluralism. That’s democracy.

That’s also what it means to earn one another’s votes.

The Gerrymandering Rigamarole

Now, about those redrawn maps.

Some of my left-leaning friends have harangued me for not being all-in on “fight fire with fire.” If Republicans are going to gerrymander, they argue, Democrats should do the same. You can’t bring a knife to a gunfight, right?

I get it. Trump and allies like Texas Governor Greg Abbott are doing everything they can to tilt the field — from pressuring Republican-controlled legislatures to manipulating election rules.3

But here’s the thing: California’s independent redistricting commission, established in 2010, has shown there’s a better way.4 It’s not perfect, but it’s more transparent, more accountable, and far less partisan than when state legislatures draw the maps themselves. That’s been one of the most meaningful democratic renovations of our era.

So why would we abandon that now? If we claim to stand for fair representation, that principle has to hold even when it’s inconvenient. Otherwise, we’re just perpetuating the very toxicity we claim to fight.

The Alternative: Earn Their Votes

There’s another way to win, and it doesn’t involve rigging the system. It involves doing the work.

Go into those newly drawn districts — the ones in Texas, Missouri, North Carolina and Ohio — and listen to the people who live there. Then craft messages and policies that respond to what they actually care about.

That’s what Arizona Senator Ruben Gallego did. He didn’t run as a caricature written by national consultants or as the “Democrat Party” boogeyman you’d see on cable news. He talked about border security, about veterans, about the economy — issues that matter to Arizonans. He refused to use jargon like “Latinx,” not because he’s anti-inclusion, but because he wanted to connect with voters where they are.5

And it worked. In a purple state, he earned enough trust to win — not by changing who he is, but by showing respect for who his constituents are.

Now, imagine applying that approach in the Rio Grande Valley or in areas where there are other newly drawn districts. These aren’t monolithic regions. Even in so-called “redrawn Republican strongholds,” there are persuadable voters. Beto O’Rourke actually would have won three of the five newly drawn districts now considered safely Republican in Texas — as recently as 2018.6

The math of gerrymandering is never absolute. When mapmakers shift lines to make one district safer, they make others thinner at the margins. A few percentage points of persuasion — or turnout — can make the difference.

So again: EARN THEIR VOTES.

The Moral of It All

You want to end the shutdown? Earn their votes.

You want to win competitive districts? Earn their votes.

You want to rebuild trust in a broken system? Earn our votes.

Democracy doesn’t die when we disagree. It dies when we mistake 80% progress for total defeat. It dies when we turn policy differences into personal enmity. It dies when we see opponents as enemies, and neighbors as avatars for parties. It dies when we give up on persuasion and assume “they” only want the worst for the country we all share.

Reviving democracy starts the same way it always has: with the forbearance to grasp the strongest arguments of those who disagree, the courage to endure the fiercest objections from our own ranks, and the daily work of restoring faith in one another.

And that’s how we can begin to earn one another’s votes.

Footnotes

“Filibuster and Cloture in the Senate,” Congressional Research Service.

Jonathan Rauch, Cross Purposes: How We Can Get Beyond Political Tribalism and Rebuild Civic Trust (Brookings Institution Press, 2024).

Michael Li, “Gerrymandering Explained,” Brennan Center for Justice.

“Assessing California’s Redistricting Commission: Effects on Partisan Fairness and Competitiveness,” Public Policy Institute of California.

Kathryn Watson, “Democrats are losing Latino men. Ruben Gallego has advice on winning them back.” CBS News, Nov. 12, 2024.

Mike Madrid and Gustavo Arellano, “Latinos and redistricting: Why both parties can’t draw themselves out of their Latino problem,” The Great Transformation.

This => [The filibuster] ensures that even when one party controls both chambers and the presidency, the minority still has a seat at the table. “Elections have consequences” is true — but in a representative democracy, those consequences don’t mean absolute rule by 50% + 1.

So, what’s the answer? The majority in the Senate could, at any time, earn enough votes from their colleagues across the aisle to reach that 60-vote threshold. Negotiate. Concede where necessary. Govern.

That’s not radical. That’s the system working as intended.

Excellent essay!